Sei Research Initiative

The Generations of Consensus: From Safety-first to Instant Finality

Dec 11, 2025

Abstract

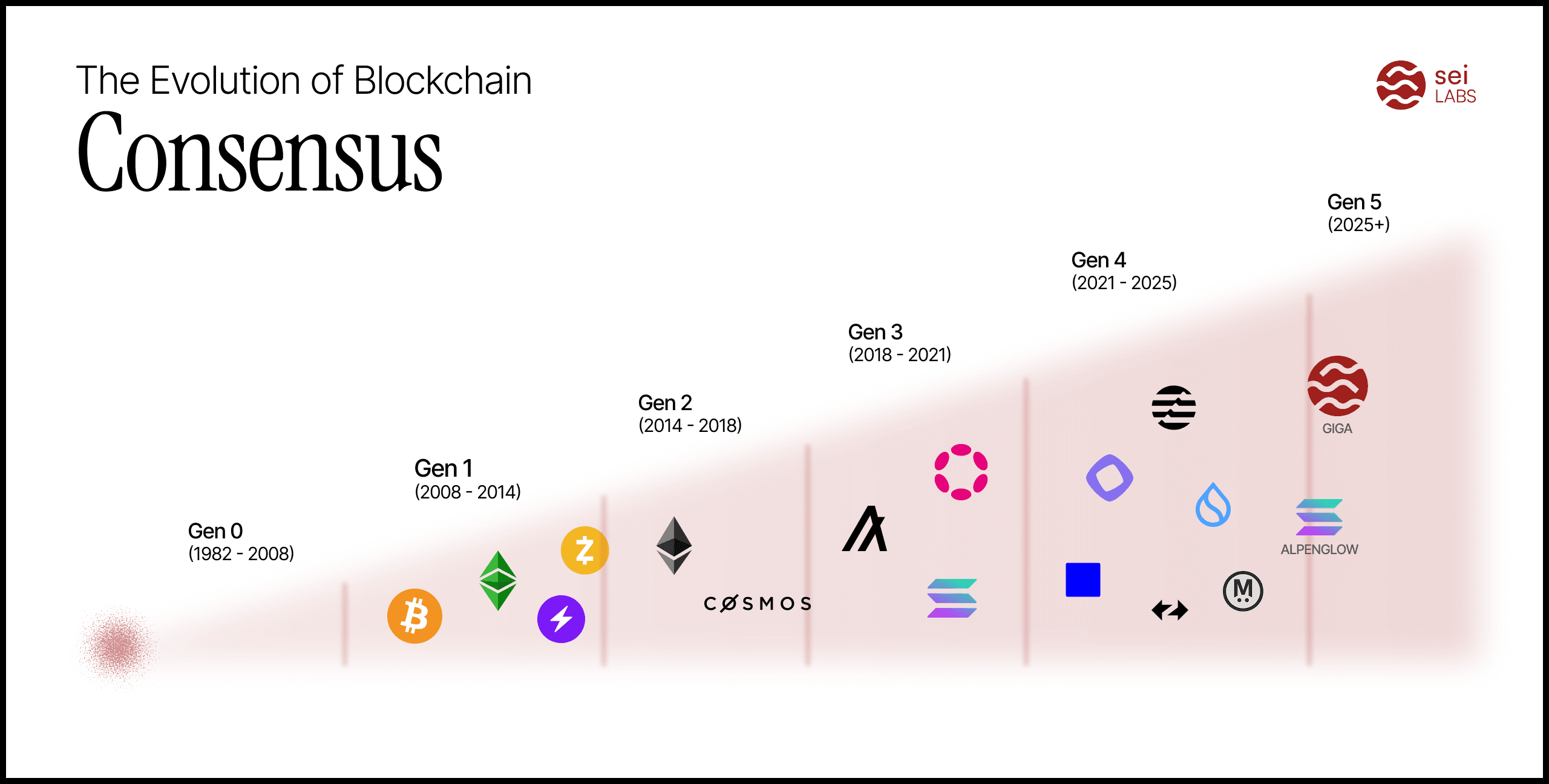

The evolution of distributed consensus, at the heart of any blockchain system, has led to a multi-generational quest to push the limits of the blockchain trilemma, the (alleged) impossibility of simultaneously guaranteeing security, scalability, and decentralization. Early protocols (Gen 0) established Byzantine Fault Tolerance in permissioned settings but were unsuitable for open networks (scalability and security, no decentralization). The advent of Proof-of-Work (Gen 1) solved trustless Sybil resistance but sacrificed performance. Proof-of-Stake (Gen 2) brought back Gen 0 consensus protocols to the permissionless setting. Subsequent generations focused on optimizing the monolithic chain through parallelization and pipelining (Gen 3), before a paradigm shift towards decoupling data dissemination, ordering, and execution (Gen 4). The next generation (Gen 5) pushes latency to its theoretical limits with relaxed fault models (n=5f+1) and shifts focus to new bottlenecks like execution and meta-properties like MEV-resistance. The blockchain trilemma is meant to provide a common reference point for understanding the technical breakthroughs over the last decade. The underlying consensus mechanisms for distributed systems such as Sei Giga, which addresses the problem by optimizing across the entire stack, may mark a nominal end to the Trilemma Epoch, after which a new set of tradeoffs will define how progress is measured.

Summary

The history of distributed consensus is a multi-generational quest to breach the theoretical limits of the blockchain trilemma. This chronicle traces the evolution of trust from centralized control to global, instantaneous agreement. We characterize the history of consensus in the following ages:

0. The Classical Age (1982–2008). This era laid the secure, yet closed, foundations of Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT). Consensus was the domain of known participants. Hierarchical systems lacking any pretense of decentralization. This time set the bounds, metrics and assumptions for years to come.

1. The Reformation Age (2008–2014). The paradigm shifted with Proof-of-Work (PoW) solving trustless Sybil resistance. This breakthrough achieved unprecedented Decentralization and Security but exacted a heavy toll on performance, imposing long, probabilistic finality. This era is transgressive and ignores many of the results from the classical age.

2. The Renaissance Age (2014–2018). Proof-of-Stake (PoS) provided the necessary economic scaffolding, resurrecting BFT protocols and liberalizing the classical, permissioned validator role. This generation restored deterministic finality (often in seconds) and higher throughput.

3. The Industrial Age (2018–2021). Focused on monolithic optimization, this age was defined by the Iron Curtain division between those championing maximum Scalability (like Solana) and those doubling down on core Security (like Ethereum). Protocols pushed the single chain to its limit using pipelining and parallelization, achieving new benchmarks in latency.

4. The Enlightenment Age (2021–2024). The monolithic structure was finally broken. This shattering of the traditional consensus structure separating dissemination, ordering, and execution, effectively solved the throughput bottleneck, exposing state execution as the new constraint. The division from the iron curtain continued, but breakthroughs were largely orthogonal and applicable to both sides.

Next generations: The Nuclear Age (2025–Current). The current frontier is the race for the lowest possible latency. This requires challenging the optimal n=3f+1 security bound (tolerating less than 33% of the stake controlled by attackers) with relaxed fault models (e.g., n=5f+1, which reduces the tolerance to less than 20%) in order to achieve optimal latency (e.g. in the n=5f+1 model good case latency takes two consensus steps: propose and prevote, not needing the precommit phase). However, this ambition is shattering the foundations of the classical era, much like how nuclear physics split the atom, with likely more exotic security models and assumptions (i.e. the paradox of safety), as protocols race to the bottom of best and common/worst case latency, which are still at direct odds.

Preliminaries: Limitations and Metrics

The main challenges and desirable features of blockchains have widely been simplified into a three-way trade-off, known as the blockchain trilemma . This trilemma establishes a trade-off between three properties: security, scalability, and decentralization. First, security refers to the properties that a blockchain guarantees in the presence of attacks against the underlying network, by members of the system, or a mix of both. Second, scalability defines the capacity of a blockchain to produce high throughput, measured in either transactions or gas per second, and latency. Third, decentralization ensures that every user of the blockchain service can also offer it.

The quest for a perfect blockchain in the informal trilemma terms is fundamentally constrained by a set of well-established theoretical limits:

The CAP Theorem and BFT Consensus: the CAP Theorem dictates that a distributed system cannot simultaneously guarantee Consistency, Availability, and Partition tolerance. Since network partitions are unavoidable in decentralized systems, blockchains must trade between perfect consistency and constant availability . This tension is formalized in Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT) research. The seminal FLP impossibility result proved that in a purely asynchronous network (with no time bounds on message delivery), deterministic consensus is impossible even with a single crash fault . To build practical systems, protocols assume partial synchrony (messages are eventually delivered) , but even here, a hard security bound exists: Dwork, Lynch, and Stockmeyer proved consensus is impossible if an adversary controls one-third or more of the power (stake) (n<3f+1 where n is the total power and f the power controlled by the adversary), with a relaxed impossibility bound of n<2f+1 for the synchronous case (which already trades latency for safety). This result underpins the security model of all protocols that solve consensus, like Blockchains.

Bit Complexity (Scalability vs. Decentralization): Any Byzantine agreement protocol requires at least Ω(n²) bits of communication in the worst case, a fundamental lower bound proven by Dolev and Reischuk. This quadratic complexity creates a direct conflict between scalability and decentralization. As the number of participants (n) increases to enhance decentralization, the communication overhead grows exponentially, hindering throughput and increasing hardware requirements for each node . Civit et al. tightened the bound to bit-level by Ω(nL+n²) for consensus on an L-bit value .Latency Limits (Performance Trade-offs): The speed of consensus, measured in message delays, is also bounded. Leader-based protocols can achieve optimistic latency of two steps (e.g. propose, prevote) in the best case, which can be pipelined. However, leaderless protocols, while more resilient to single-point failures, typically require at least 3 consensus steps to resolve conflicts when multiple differing proposals are made concurrently . This establishes a core trade-off between best-case speed and worst-case resilience, that is critical to understand for the more recent generations of consensus.

Fairness Impossibility (Decentralization Challenges): True decentralization requires not only a large number of participants but also fairness, preventing any small group from systematically biasing outcomes. This is especially true of systems like Proof-of-Stake (more so with inactivity leaks) where membership is endogenously defined, and an unfair advantage in outcomes can compound over time even in membership control: an attacker slowly taking over the entire membership. However, achieving fair protocols that are robust to strategic, self-interested participants is notoriously difficult. Halpern and Vilaça showed that no fair consensus protocol can be an ex post Nash equilibrium if even a single crash failure is possible .

The above results help support the intuition of the trilemma. Nevertheless, there have been smart workarounds through these years that bypass the limits here outlined, such as avoiding consensus for payments, or horizontal scalability solutions like payment channels, subnets or the prominent rollups, all of which we will mention later.

A Formalization of the Trilemma

We speak of the blockchain’s upload speed Q_up as the number of distinct transactions per second (tps) that a user sends to processes. We use Q_do to refer to the download speed of the blockchain, which is the number of finalized transactions per second. All users must verify (execute) finalized transactions locally for correctness, in that all finalized transactions are valid given the current state of the blockchain, and compute the resulting state. We then speak of the verification speed of a blockchain Q_ver, as some representative metric of the verification speed of all of its users (e.g. average, median, some percentile), and same construct is applied for the download speed. Having defined these terms, we now propose a definition of the blockchain trilemma. The purpose of this definition is to set a goal for blockchains, in that a perfect blockchain would guarantee these three properties.

Definition (Blockchain trilemma). A blockchain Ωsolves the blockchain trilemma if it satisfies the following properties:

Scalability. Ω finalizes blocks such that Q_do ≥ min(Q_ver, Q_up).

Decentralization. Any user can become a process and have his proposals finalized with non-null probability.

Security. Ω implements state machine replication (SMR).

Proposition 1 (Impossibility of the Trilemma). It is impossible to solve the blockchain trilemma.

Sketch. A secure blockchain that guarantees a consistent ordering of finalized blocks has a consensus number of ∞. Any resilient-optimal, Byzantine fault-tolerant protocol that solves distributed consensus has a bit complexity of at least O(n²). Assuming a non-trivial computation time to verify blocks, this quadratic communication overhead inherently conflicts with the goal of unbounded scalability and decentralization, where any user can participate without prohibitive hardware or bandwidth requirements . True decentralization is hindered by the impossibility of having a fair consensus protocol if even a single crash failure is possible , allowing rational agents to strategically bias outcomes, which can be used to take control of decentralization over long-enough periods of time.

This inherent tension has driven a generational evolution, with each new wave of protocols making different trade-offs to push the frontier of what is possible, and breakthroughs optimizing resources.

Metrics of Interest

Beyond the empirical metrics that we are all familiar with, i.e. transactions per second, gas per second and the types of latencies (end-to-end, blocktime, or finalization, good case, common case, and worst case) per number of validators, we discuss below theoretical metrics too, as they help compare protocols in a vacuum, unlike empirical measurements. The purpose is for the reader to build an informative view of how to properly compare fundamentally different consensus protocols and their position in the trilemma.

Theoretical Scalability Metrics

Time Complexity: This classic metric measures the number of message delays required to reach a decision. This minimum delay establishes the ultimate limit on how fast a consensus decision can be made in terms of network communication rounds. The number of message delays can be considered in the amortized case (through pipelining).

Bit Complexity: This family of metrics refines the traditional Bit Complexity, which measures the total number of bits exchanged, with Ω as the theoretical lower bound for BFT consensus. These advanced metrics provide a more accurate view of a protocol’s throughput and scalability in practice:

Normalized: This is the total bit complexity divided by the number of outputs per consensus instance. It correctly compares efficiency: a protocol with O(n³) complexity that finalizes Ω(n) blocks per round (Normalized O(n²)) is more scalable than one that only finalizes O(1) blocks (Normalized O(n³)).

Amortized: This provides a realistic long-term performance view by averaging the cost over many rounds. The high cost of a failure is amortized over subsequent successful rounds, assuming the adversary is static or slowly-adaptive. For example. partially synchronous leaderless protocols guarantee decisions in every round when synchrony is met, whereas a leader-based protocol with a faulty leader may lead to several rounds without decision.

Per-Channel: This is critical for real-world network performance. While a protocol may have an optimal overall O(n²) complexity, routing most of that traffic through a single leader creates a network bottleneck. Leaderless protocols distribute the load of bits sent across all Ω(n²) network channels, which scales much better in practice (though this is for the all-to-all pairwise channels model, a similar approach can be applied to the gossip network model).

Security and Decentralization Metrics

Network and Adversarial Assumptions: This defines the core security model. Does the protocol assume synchrony (a known upper bound on message delay) or the more realistic partial synchrony? . Crucially, what is the fault tolerance, the number of Byzantine participants f the system can withstand, typically f<n/3 in partial synchrony , with some works in synchrony assuming f<n/2, while others assume f<n/5 due to low latency pressures or because of resorting to committee sortition.

Economic Security & Decentralization: In open, permissionless systems, security is not just about the number of nodes but the economic cost for an adversary to compromise them. Decentralization is measured by the number of independent, non-colluding entities required to solve consensus and the rules established to allow clients to become one of these entities (e.g. sortition among stakers).

Cryptographic Assumptions: Security often relies on standard cryptographic primitives like digital signatures . More advanced protocols may require stronger, newer assumptions like Verifiable Delay Functions (VDFs) or bilinear pairings , which can introduce different security trade-offs.

Generation 0: The Classical Age

The quest for distributed consensus predates blockchains by decades. Early pioneering work focused on achieving agreement among a known, fixed set of participants in environments like distributed databases or fault-tolerant enterprise systems. Protocols like Paxos (Crash Fault Tolerant) , PBFT or Zyzzyva (Byzantine Fault Tolerant) established the theoretical foundations and practical algorithms for reaching consensus even when some participants fail. However, these Generation 0 systems operated in permissioned settings. Membership was controlled externally, typically by a central administrator or consortium, defining who could participate. There was no mechanism to handle an open, dynamic set of participants joining and leaving freely, nor was there a need to resist Sybil attacks, where a malicious entity could easily create countless fake identities to overwhelm the consensus. While secure and relatively performant within their walled gardens, these protocols were fundamentally unsuited for the trustless, open environment envisioned for cryptocurrencies. The formal origin of this problem space dates back to the 1980s with the Byzantine Generals Problem . From a metrics perspective, these protocols set the baseline:

Security & Network: They typically operate under the partially synchronous or asynchronous model (the same model used by most PoS chains today) and proved that security (consistency) was possible as long as the number of faulty participants f is less than one-third of the total n=3f+1.

Bit Complexity: Their performance is acceptable only for small, fixed committees. PBFT’s normal-case bit complexity is O(n²), matching the theoretical lower bound.

Time Complexity (Latency): Latency was a secondary concern. Protocols like PBFT may require significant message delays to confirm a decision . While speculative-execution protocols like Zyzzyva attempted to optimize this for the good case , the focus was overwhelmingly on safety over liveness.

Decentralization & Economic Security: These metrics were non-existent. Security was based on fault count, not economic cost, as participants are assumed to be known entities.

This combination, permissioned membership, low scalability (n was small), and a non-economic security model, placed Gen 0 firmly in the Security & Scalability vertex of the trilemma, with no decentralization. Consensus in this space took analogies from generals organizing in battle, with a clear hierarchical structure in a closed system. Bitcoin was about to shatter those analogies.

Generation 1: The Reformation Age

The paradigm shifted dramatically in 2008 with the arrival of Bitcoin . Satoshi Nakamoto’s key innovation was Proof-of-Work (PoW), a mechanism providing trustless Sybil resistance. By requiring participants (miners) to expend real-world resources (computation, energy), PoW made creating fake identities prohibitively expensive, enabling consensus in an open, permissionless network for the first time . Bitcoin combined PoW with the longest chain rule (or heaviest chain) to achieve Nakamoto Consensus . This Generation 1 approach solved the core problem of decentralized agreement but came with significant trade-offs. Consensus provides only probabilistic finality (eventual consensus) ; certainty about a transaction’s irreversibility increases over time but is never absolute . Off-chain actions relying on transaction finality often require waiting from tens of minutes to hours for sufficient block confirmations in these systems. Furthermore, the sequential block production inherent in PoW proved difficult to scale, leading to low throughput. Despite these limitations, PoW powered the first wave of successful blockchains, including Ethereum (pre-merge) , Litecoin, Monero , and Zcash . These foundational PoW chains have seen remarkably few changes to their core protocols over time.

This generation also saw the first emergence of meta-properties, features beyond simple agreement. While Bitcoin offered pseudonymity, new chains like Monero and Zcash were engineered specifically for privacy, using advanced cryptography like ring signatures and zk-SNARKs to obscure senders, receivers, and amounts.

Concurrently, the stark performance limits of the base layer spurred the first major approaches to scalability. These were not base-layer changes but the first Layer-2 (or off-chain) protocols. Concepts like payment channels, channel factories , and payment channel networks (famously, the Lightning Network) were developed to move high-frequency, low-value transactions off the main chain, bypassing the consensus bottleneck. In the blockchain trilemma, Generation 1 made an unambiguous trade-off: it achieved unprecedented Decentralization and robust Security at the direct expense of Scalability . The key metrics of interest for this generation thus shifted away from Gen 0’s fault counts.

Security focused on exogenous, economic properties, exemplified in hashrate and the cost to attack (i.e., acquiring 51% of network hash power). Decentralization thus became the centerpiece of Gen 1 blockchains.

Scalability (Throughput) is low in these systems, measured in single-digit transactions per second (TPS).

Scalability (Latency) did not yet become a system property for off-chain actions in these systems. It was defined by probabilistic finality, requiring users to wait for multiple block confirmations (e.g., 6 blocks, or ~1 hour) to gain sufficient confidence that a transaction was irreversible.

Thanks to PoW, Sybil could not disguise anymore, and not just generals but anyone could take power in the system. A new breakthrough in Proof-of-Stake would bring Sybil resistance bring a renaissance age to the classical protocols. The general role was up for grabs.

Generation 2: The Renaissance Age

The performance limitations and energy consumption of PoW spurred the development of Proof-of-Stake (PoS) . This Generation 2 innovation replaced computational work with economic stake as the scarce resource for Sybil resistance . Validators lock up capital (stake) within the network, and their consensus participation rights (and potential penalties for misbehavior via slashing) are proportional to their stake . The threat of slashing their endogenous resources secures their behavior. However, not all PoS systems immediately adopted classical BFT. An alternative branch, including systems like Filecoin (which, though it uses Proof-of-Spacetime, it contains membership as part of the state of the system, like PoS) or Ethereum’s PoS , used stake (or other proven resources) primarily as a Sybil resistance mechanism for a chain-based protocol.

In this model, validators are chosen to produce blocks, but the canonical chain is determined by a fork-choice rule, much like PoW’s heaviest chain, rather than a multi-round BFT vote. This approach, much like Generation 1, provides probabilistic finality (eventual consensus) and prioritizes liveness, but it lacks the fast, deterministic finality of its BFT-based counterparts.

Nevertheless, having explicit membership as part of the state of the system, like PoS does, enabled the return of classical BFT consensus algorithms (from Gen 0) to the permissionless world. By using stake to manage participation, protocols like Cosmos’s Tendermint , Cardano’s Ouroboros , and later Ethereum’s Gasper could achieve much higher throughput and faster finality (often deterministic within seconds) compared to PoW chains. PoS also introduced different security considerations, notably the risk of long-range attacks , which PoW is less susceptible to due to its reliance on continuous computational history. At the same time, though, the exogenous security of PoW is vulnerable to risks not present in PoS chains, such as the ability for miners to instantly redirect their computational resources to attack other compatible chains (migratory hash power) without facing any direct, in-protocol economic penalty on the chain they just left.

This generation also saw the first major attempts at native scalability improvements beyond simply faster consensus. Committee sortition emerged, where a smaller, rotating subset of the total validator set is randomly chosen to run the consensus protocol for a period . This maintains decentralization (in theory, anyone with stake can be chosen) while bounding the communication overhead (n remains constant) .

As a result, new competing paradigms started to appear in the space. BFT-based PoS protocols like Tendermint are C-preferring, prioritizing Consistency over Availability; if a network partition or massive outage makes more than 1/3 of validators unreachable, the chain halts to prevent any possibility of a fork . In contrast, chain-based protocols (both PoW and non-BFT PoS) are A-preferring, prioritizing Availability. They continue to produce blocks even during partitions, which results in forks that are resolved later. This fundamental choice dictates whether a system offers fast, deterministic finality or liveness under extreme network conditions.

The increased programmability of Generation 2 chains like Ethereum also fueled a new wave of Layer 2 research. While Gen 1 had payment channels for simple value transfers, Gen 2 saw the rise of more complex horizontal scalability solutions like sidechains and childchains (e.g., Plasma), which were direct conceptual ancestors to the modern rollup-centric roadmap. With this generation, the metrics of interest became more sophisticated.

Security: Security remained economic, but shifted from hashrate to the total value of staked capital and the economic cost required to corrupt the 1/3 (for BFT) or 51% (for chain-based) of validators.

Scalability (Throughput): This saw a dramatic leap, moving from single-digit TPS to systems capable of handling hundreds or thousands of transactions per second.

Scalability (Latency): The most significant change was the introduction of deterministic finality. Instead of waiting hours for probabilistic confirmation, BFT-based PoS chains could finalize transactions in seconds.

Decentralization: This was no longer just about node count but also about the distribution of stake. Metrics like the Nakamoto Coefficient or the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) emerged to measure the concentration of power among validators .

Protocols like Tendermint became the archetype for this generation. They successfully imported classical BFT into a permissionless model by mapping security to economic stake, offering fast, deterministic finality and high throughput in a way that was previously impossible in an open system. Alongside other major protocols like Cardano’s Ouroboros, Algorand, and Ethereum’s Gasper, this generation established the dominant BFT-over-PoS design that defined the trilemma trade-offs for years to come.

As the renaissance brought classical protocols to compete with those of the reformist age, consensus protocols prepared to focus on pushing the limits of the trilemma in this paradigm. But as it often happens in cultures, a subdivide took place between two competing forces, that drew an iron curtain between them. The stage was set for mass production on both ends.

Generation 3: The Industrial Age

With PoS established, Generation 3 focused on optimizing the performance of the single, monolithic blockchain . The goal was to squeeze more throughput and lower latency, with techniques like parallel proposals on a single chain (for lower normalized complexity and same per-channel complexity), or pipelining (for lower amortized complexity), but without yet decoupling execution, consensus and data dissemination. The first considerations of trading decentralization or security in favor of performance started to appear. Solana and its Proof-of-History emerged in this context. PoH timestamps transactions before they are submitted to a consensus protocol known as Tower BFT. This pre-ordering of events drastically reduces the communication overhead needed for validators to agree on a sequence, enabling massive parallelization in transaction processing and leading to headline-grabbing throughput figures.

Solana’s approach took the space by storm. While the formal correctness of its full model was (and remains) debated, its apparent success in production, demonstrating sub-second finality and tens of thousands of TPS, fundamentally changed the priorities of the space. The trilemma debate shifted: instead of prioritizing security and decentralization first, Solana championed scalability first. This mentality became a dominant narrative that persists today in a majority of the crypto space. As is often the case in systems relying on security, the paradox of safety played its part and the design philosophy of the entire industry split:

One camp, now including other high-performance chains, followed Solana’s lead, relaxing security and decentralization as a necessary trade-off for web-scale performance.

The other camp, captained by Ethereum, doubled down on robust security and decentralization, arguing that true resilience was paramount, even at the cost of base-layer performance.

Other key innovations helped alleviate the trilemma on both ends of this spectrum, including:

Pipelining: Techniques like those in Pipelined HotStuff aimed to improve steady-state throughput by overlapping communication stages across different consensus instances, effectively allowing a new decision potentially every message delay after an initial setup phase.

DAG-based Approaches: Protocols like HoneyBadgerBFT explored Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) instead of linear chains for transaction ordering, allowing for some degree of parallel processing and censorship resistance, though often in asynchronous settings.

Communication Optimizations: Research focused on reducing the practical impact of the O(n²) communication complexity, for instance, by designing protocols mindful of per-channel complexity to avoid bottlenecks on specific links in realistic network topologies.

This iron curtain between these two competing visions persist today, but the next generation of consensus is actually characterized by improvements that mostly benefit both sides, in what we call the Enlightenment Age.

Generation 4: The Enlightenment Age

With the spectrum of competitors between performance and security/decentralization defined, the race to reach the best of the disregarded properties from each side started. Having competitors on the other side of the spectrum, pressure to win the argument increased. Most of the breakthroughs at this time still proved beneficial across the space. An example of this is the decoupling between data dissemination, ordering, and execution, allowing each component to be parallelized and optimized independently. The canonical example is Narwhal , which serves as a high-throughput data availability layer that reliably disseminates and orders transactions for a separate consensus protocol to later finalize.

With this decoupling, the practical requirements transaction throughput were effectively reached (in comparison with other steps of the critical path, like execution), shifting the focus of the consensus bottleneck. The pressure on achieving the lowest possible latencies for finality increased even more as a result. Ethereum’s rollup-centric roadmap allowed it to play hands on both sides of the spectrum: while the main L1 chain continues to prioritize decentralization and security, the ecosystem embraced rollups to handle the demand for high-performance execution, augmented by out-of-protocol features like preconfirmations, which aim to provide fast, off-chain finality guarantees that settle on the secure L1. Rollups, while initially more supportive to decentralization of sequencers, has in most cases degenerated into less decentralized and more scalable (with notable examples in MegaETH , Base , or Arbitrum ), with only a small number of proposals in the space advocating for decentralization of L2 layers (ZKSync’s ChonkyBFT , or Espresso’s HotShot ).

Sei originated as a Gen 3 blockchain, progressing to Gen 4 with the advent of Twin Turbo Consensus (an optimization of Tendermint ), which pushed the limits of the single-chain model, achieving deterministic finality in under 400 ms.

Twin-Turbo accomplished this through two core optimizations: Intelligent Block Propagation (reducing network wait time by gossiping compact block proposals) and Optimistic Block Processing (simultaneously executing transactions during the consensus voting phases). This aggressive optimization reduced the time to finality to speeds comparable to traditional Web2 applications, establishing a new benchmark for monolithic L1 latency.

This generation of decoupling steps and layers of consensus had a profound impact on the properties of the trilemma:

Security & Network: The core security model (e.g., n=3f+1 in partial synchrony) remains on the consensus layer, but the system’s overall security now also depends on the integrity of the links between layers. A new, critical security concern emerged: Data Availability (DA). The consensus layer must guarantee that all data for L2s is published and accessible, preventing data withholding attacks where a malicious producer could steal funds .

Scalability (Throughput): This is where the decoupling shines. New data dissemination layers, when paired with a consensus protocol like HotStuff, demonstrated throughput of 100,000 transactions per second, which shattered previous monolithic limits.

Scalability (Latency): Latency became a more nuanced trade-off. While the decoupled data dissemination maintained high throughput, the finality time was still dependent on the consensus protocol it was paired with.

Sei Giga and its consensus inspiration, Autobahn, are the culmination of this generation focused on decoupling. Concretely, Sei Giga achieves (i) responsive data dissemination while (ii) streamlining finality through their decoupled design that relies on Consistent Broadcast. Internal devnet tests demonstrated a sustained capacity of 5 Gigagas (over 5.4 billion Gas/sec) with a finality of approximately 700ms in a globally distributed 40-node network. Autobahn thus positions Sei Giga as the leader in seamless, high-speed BFT of this generation.

The great decoupling has brought incredible performance to consensus. As latency is to be pushed further, the space has most recently turned to assumptions and models that had not been debated since the Classical Age set them, opening a Pandora’s box of new models and assumptions in an effort to claim the lowest latency available, much like the Nuclear Age split the atom.

Next Generations: The Nuclear Age

One could argue we are still in the age of the Enlightenment, and it is indeed not immediate to make a sharp separation between ages. However, a new, critical difference merits a new age: the breaking of the n=3f+1 bound for off-chain actions, and the definition of new communication models. Up until recently, all previous generations assumed n=3f+1 or n=2f+1, with exceptions required by the need to resort to committees that roughly security to 20% Byzantines out of all the participants (not the n in the consensus that the sorted participants run). Similarly, communication models like granular synchrony are gaining traction.

The race to the bottom of latency has forced a split on the atom that made the cornerstone of BFT consensus up until recently. Initially considered in research, Solana’s Alpenglow has become the first L1 with high impact to announce a vision in a model that explicitly assumes n=5f+1 (meaning even lower tolerance if they ever resort to committees). This assumption is interesting because it allows achieving optimal latency in the good case for leader-based BFT protocols .

However, these protocols are still to solve a critical problem that becomes apparent when best/good case latency becomes so fast: worst case (or tail) latency. Leader-based protocols are exceptionally fast when the leader is honest and the network is stable, but they perform poorly under faults or network instability, often requiring slow view-changes. Systems that must rely on low latency cannot afford to have unpredictable events of high tail-latency. We are already seeing mounting counter-pressure from leaderless designs, which offer better resilience and more predictable performance in the worst case, though typically at the cost of a slower best-case path, and that can also benefit from the n=5f+1 model. We formalize below the limitations of the current design space:

Proposition 2 (Leader-based Optimality). In the good case (a correct, stable leader and timely network messages), a leader-based BFT protocol decides in two message delays. This can be pipelined to achieve an effective one-message delay for repeated consensus.

Proposition 3 (Leaderless Resilience). In a leaderless BFT protocol, concurrent and differing proposals typically require 3 message delays to resolve conflicts in the proposals from nodes, except under ideal conditions.

Perhaps the future of consensus will be a hybrid synthesis: a protocol that operates in a fast, leader-based mode by default, but features a highly accurate and extremely fast mechanism to switch over to a new leader, or a leaderless fallback, the moment a fault is detected.

As Pandora’s box has opened, novel security models that justify these latency gains but also alleviate the threat to security in some form are emerging. We are seeing protocols move beyond standard partial synchrony, such as by assuming a 2f synchronous assumption, or the more exotic assumptions seen in Alpenglow, Kudzu’s flexible fault tolerance or MonadBFT’s speculative execution . Interestingly, the move to larger quorums like n=5f+1 also provides a stronger foundation for accountability .

New network and fault models are likely to keep coming out of Pandora’s box. We may see protocols that, in the presence of a majority coalition, choose to prioritize liveness over strict safety. This would allow for temporary forks (eventual consensus) but with the guarantee of detecting faults, punishing attackers, and converging back to a single, consistent state, a model that has recently been explored .

With consensus ordering transactions at unprecedented speeds, state execution remains critical for performance. This is driving a new wave of innovation entirely focused on parallel execution engines and efficient state verification.

Finally, as the space for big impact innovation on the main properties of latency and throughput gets narrower, proposals are starting to focus on meta-properties, like end-to-end latency, privacy, accurate pricing or replication factors for data availability.

Regarding consensus-specific innovation, the future for Sei will provide an unprecedented combination of optimal best case and ridiculously low worst case latency, critical for reliable systems. We are also working on enhancing features, performance and security through the careful studying of critical meta-properties, like censorship or MEV resistance. Despite the incredible journey of consensus protocols so far, research interest in consensus has only grown each year, and many more innovations are to keep coming long after, both at Sei and in the space.

Join the Sei Research Initiative

We invite developers, researchers, and community members to join us in this mission. This is an open invitation for open source collaboration to build a more scalable blockchain infrastructure. Check out Sei Protocol’s documentation, and explore Sei Foundation grant opportunities (Sei Creator Fund, Japan Ecosystem Fund). Get in touch - collaborate[at]seiresearch[dot]io

References

[1] G. Aggarwal, F. Sch¨ar, and G. Fanti. An empirical analysis of stake concentration in proof-of-stake-blockchains. In 2021 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), pages 1475–1491, 2021. doi: 10.1109/SP49788.2021.00087.

[2] M. Al-Bassam, B. B¨unz, and S. Micali. Fraud and data availability proofs: Detecting invalid blocks in light clients. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS), pages 2185–2200, 2019. doi: 10.1145/3319535.3345638.

[3] Base Team. Introducing base. https://base.org/blog/introducing-base, Feb 2023.

[4] C. Baum, B. David, R. Dowsley, J. B. Nielsen, and S. Oechsner. Craft: Composable randomness and almost fairness from time. IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive, 2020:284, 2020.

[5] E. Ben-Sasson, A. Chiesa, C. Garman, M. Green, I. Miers, E. Tromer, and M. Virza. Zerocash: Decentralized anonymous payments from bitcoin. In 2014 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), pages 459–474, 2014. doi: 10.1109/SP.2014.36.

[6] V. Buterin. Long range attacks: The serious problem with adaptive proof-of-work. Blog post, 2014.

[7] V. Buterin. Why sharding is great: demystifying the technical properties. https://vitalik.ca/general/2021/04/07/sharding.html, 2021.

[8] V. Buterin and V. Griffith. Casper the friendly finality gadget. arXiv preprint arXiv: 1710.09437, 2019.

[9] M. Castro and B. Liskov. Practical byzantine fault tolerance. In Proceedings of the Third Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI), pages 173–187, 1999.

[10] Brendan Kobayashi Chou, Andrew Lewis-Pye, and Patrick O’Grady. Minimmit: Fast finality with even faster blocks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.10862, 2025.

[11] P. Civit, S. Gilbert, V. Gramoli, R. Guerraoui, and J. Komatovic. As easy as abc: Optimal (a)ccountable (b)yzantine (c)onsensus is easy! In 2022 IEEE 36th International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS), pages 30–39, 2022. doi: 10.1109/IPDPS54754.2022.00018.10

[12] T. Crain, V. Gramoli, M. Larrea, and M. Raynal. Dbft: Efficient leaderless byzantine consensus and its application to blockchains. In 2018 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Network Computing and Applications (NCA), pages 1–8, 2018. doi: 10.1109/NCA.2018.8475510.

[13] G. Danezis, L. Kokoris-Kogias, A. Sonnino, and A. Spiegelman. Narwhal and tusk: A dag-based mempool and efficient bft consensus. In Proceedings of the 17th European Conference on Computer Systems (EuroSys ’22), pages 1–19, 2022. doi: 10.1145/3492321.3519597.

[14] S. Das, V. Krishnan, I. M. Isaac, and L. Ren. Spurt: Scalable distributed randomness beacon with transparent setup. In 2022 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), pages 1536–1554, 2022. doi: 10.1109/SP49788.2022.00096.

[15] B. David, P. Gaˇzi, A. Kiayias, and A. Russell. Ouroboros praos: An adaptively-secure, semi-synchronous proof-of-stake blockchain. In Advances in Cryptology - EUROCRYPT 2018, pages 663–690, 2018. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-78381-9 24.

[16] D. Dolev and R. Reischuk. Bounds on information exchange for byzantine agreement. Journal of the ACM (JACM), 32(1):191–204, 1985. doi: 10.1145/2455.2470.

[17] C. Dwork, N. Lynch, and L. Stockmeyer. Consensus in the presence of partial synchrony. Journal of the ACM (JACM), 35(2):288–323, 1988. doi: 10.1145/4228.4237.

[18] M. J. Fischer, N. A. Lynch, and M. S. Paterson. Impossibility of distributed consensus with one faulty process. Journal of the ACM (JACM), 32(2):374–382, 1985. doi: 10.1145/3828.3838.

[19] A. Gervais, G. O. Karame, K. W¨ust, V. Glykantzis, H. Ritzdorf, and S. Capkun. On the security and performance of proof of work blockchains. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS), pages 1054–1068, 2016. doi: 10.1145/2976749.2978370.

[20] Y. Gilad, R. Hemo, S. Micali, G. Vlachos, and N. Zeldovich. Algorand: Scaling byzantine agreements for cryptocurrencies. In Proceedings of the 26th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (SOSP), pages 533–550, 2017. doi: 10.1145/3132747.3132750.

[21] S. Gilbert and N. Lynch. Brewer’s conjecture and the feasibility of consistent, available, partition-tolerant web services. ACM SIGACT News, 33(2):51–59, 2002. doi: 10.1145/584865.584873.

[22] Neil Giridharan, Florian Suri-Payer, Ittai Abraham, Lorenzo Alvisi, and Natacha Crooks. Autobahn: Seamless high speed bft. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGOPS 30th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, SOSP ’24, page 1–23, New York, NY, USA, 2024. Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9798400712517. doi: 10.1145/3694715.3695942. URL https://doi.org/10.1145/3694715.3695942.

[23] O. Goldreich. Foundations of Cryptography: Volume 2, Basic Applications. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

[24] R. Guerraoui, P. Kuznetsov, M. Monti, M. Pavloviˇc, and D. A. Seredinschi. The consensus number of a cryptocurrency. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing (PODC), pages 415–424, 2019. doi: 10.1145/3324660.3325157.

[25] J. Y. Halpern and X. Vila¸ca. Rational consensus. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing (PODC), pages 165–174, 2016. doi: 10.1145/2933057.2933069.

[26] Harry Kalodner, Steven Goldfeder, Xiaoqi Chen, S Matthew Weinberg, and Edward W Felten. Arbitrum: Scalable, private smart contracts. In 27th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 18), pages 1353–1370, 2018.

[27] A. Kiayias, A. Russell, B. David, and R. Oliynykov. Ouroboros: A provably secure proof-of-stake blockchain protocol. In Advances in Cryptology - CRYPTO 2017, pages 328–357, 2017. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-63595-8 13.

[28] Quentin Kniep, Jakub Sliwinski, and Roger Wattenhofer. Solana alpenglow consensus, 2025. 11

[29] R. Kotla, L. Alvisi, M. Dahlin, A. Clement, and E. Wong. Zyzzyva: Speculative byzantine fault tolerance. In Proceedings of the 21st ACM SIGOPS Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (SOSP), pages 45–58, 2007. doi: 10.1145/1294261.1294268.

[30] J. Kwon. Tendermint: Consensus without mining. Whitepaper, 2014.

[31] Protocol Labs. Filecoin: A decentralized storage network. Whitepaper, 2017.

[32] L. Lamport. The part-time parliament. ACM Transactions on Computer Systems (TOCS), 16(2): 133–169, 1998. doi: 10.1145/279288.279296.

[33] L. Lamport, R. Shostak, and M. Pease. The byzantine generals problem. ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems (TOPLAS), 4(3):382–401, 1982. doi: 10.1145/357172.357176.

[34] Petar Leva, Viktor Jelisavˇci´c, Dejan Kosti´c, Oliver Gasser, and Prometej Jovanovi´c. Megaeth: A high-performance ethereum l2. In 2024 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 24), pages 807–821. USENIX Association, July 2024.

[35] Andrew Lewis-Pye and Tim Roughgarden. Beyond Optimal Fault-Tolerance. In 7th Conference on Advances in Financial Technologies (AFT 2025), Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics(LIPIcs), pages 15:1–15:23, 2025. doi: 10.4230/LIPIcs.AFT.2025.15.

[36] Jialin Lin, Zhijie Liu, Shella Lovejoy, Binhang Lyu, Ben Orlanski, Viswanath Rao, Srinivas S.,David Song, Andrew White, Yilun Zhang, and Chenfeng Zheng. Hotshot: A high-throughput bft consensus protocol for finality. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.10118, Oct 2022.

[37] Matter Labs. Chonkybft: A new consensus algorithm for zksync. https://matter-labs.io/blog/chonkybft-a-new-consensus-algorithm-for-zksync, May 2024.

[38] A. Miller, Y. Xia, K. Croman, E. Shi, and D. Song. The honey badger of bft protocols. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS), pages 535–549, 2016. doi: 10.1145/2976749.2978374.

[39] Monad Labs. Monadbft: Efficient asynchronous bft. https://monad.xyz/blog/monadbft, Aug 2023.

[40] S. Nakamoto. Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Whitepaper, 2008.

[41] J. Neu, E. N. Tas, and D. Tse. The availability-accountability dilemma and its resolution via accountability gadgets. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.06075, 2021.

[42] J. Poon and T. Dryja. The bitcoin lightning network: Scalable off-chain instant payments. Whitepaper, 2016.

[43] A. Ranchal-Pedrosa and V. Gramoli. Trap: The bait of rational players to solve byzantine consensus. In Proceedings of the ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security(ASIACCS), pages 530–542, 2022. doi: 10.1145/3538465.3538507.

[44] A. Ranchal-Pedrosa and V. Gramoli. Basilic: Resilient optimal consensus protocols with benign and deceitful faults. In IEEE 36th Computer Security Foundations Symposium (CSF), pages 617–631, 2023. doi: 10.1109/CSF57962.2023.10228399.

[45] A. Ranchal-Pedrosa, M. Potop-Butucaru, and S. Tucci-Piergiovanni. Scalable lightning factories for bitcoin. In Proceedings of the 34th ACM/SIGAPP Symposium on Applied Computing (SAC ’19), pages 30–38, 2019. doi: 10.1145/3297280.3297341.

[46] M. Rosenfeld. Analysis of hashrate-based double spending. arXiv preprint arXiv:1402.2009, 2014.

[47] Sei. How sei became the fastest blockchain: Twin turbo consensus. https://blog.sei.io/twin-turbo-consensus/, March 2024.

[48] Sei Research Initiative. Sei giga: Achieving 5 gigagas with autobahn consensus. https://

seiresearch.io/articles/sei-giga-achieving-5-gigagas-with-autobahn-consensus, Feb 2025.12

[49] V. Shoup, J. Sliwinski, and Y. Vonlanthen. Kudzu: Fast and simple high-throughput bft. In 39th International Symposium on Distributed Computing (DISC 2025), 2025.

[50] A. Spiegelman et al. Block-stm: Scaling blockchain execution by turning ordering curse to a blessing. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM SIGOPS International Conference on Virtual Execution Environments (VEE), pages 1–16, 2022. doi: 10.1145/3518116.3538183.

[51] N. van Saberhagen. Cryptonote v 2.0. Whitepaper, 2013.

[52] A. Yakovenko. Solana: A new architecture for a high performance blockchain. Whitepaper, 2018.

[53] M. Yin, D. Malkhi, M. K. Reiter, G. G. Gueta, and I. Abraham. Hotstuff: Bft consensus with linearity and responsiveness. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing (PODC), pages 346–355, 2019. doi: 10.1145/3324660.3324679.